“Learning to dive in my mid-40s felt uncomfortable. In scuba, you have to exhale more in order to sink. You have to do something that feels against self-preservation.” CEO.works Co-Founder, Shefali Salwan is no stranger to swimming in unknown waters. Shefali has lived, worked and managed change in a dual-career household across three continents. The other “careerist” is her husband and CEO.works co-founder, Sumeet Salwan.

“My career has had its ebbs and flows. At times, I felt like I was in a boat crossing a river and at others, walking along the banks. I have had to pick my battles, and suspend the ego. When you are in the middle of it, it feels messy. Looking back, I realize I have always looked to what brings me meaning and where I can have the greatest impact. This has been my steady compass.”

Placements are Pin-ball Machines

In 1994, fresh out of graduate school with an MBA specializing in Human Resources, Shefali became the first head of HR at SBI Capital. It was here in the investment banking division of the State Bank of India, the country’s largest nationalized bank that Shefali seeded her foundation in talent management. Reporting to men twice her age in a traditional culture, Shefali alternated between recruiting top talent from India’s leading business schools and establishing HR policy and practice. Shefali learned on the job and through trial by fire.

Investment banking in the 1990s was still a fledgling sector in India. Shefali’s was a new role in a bank that was known for its long legacy in Indian banking history, but unafraid to be a pioneer in frontier areas of finance such as securitization. At SBI Capital, one of Shefali’s more impactful assignments was to lobby Indian government regulators to approve a new compensation scheme so the bank could hire more competitively out of India’s top business schools.

From Recruiting Talent to “Job-Spilling”

In 1996, Salwan’s next stop was as Resourcing Manager at ANZ Grindlays. Salwan’s tenure at ANZ coincided with a massive restructuring for the bank, both financially and from a talent standpoint. The latter was achieved through “job spilling”—a practice where the entire leadership team had to reapply for incumbent positions. Alongside a direct report to the CEO, Shefali stepped in to arbitrate this critical process.

“Deciding who made the cut and who did not was difficult—it opened me to the very human side of HR.”Shefali had to reapply for her position as well. She received a double promotion—as lead HR partner for the fledgling ANZ funds management business. A few days into her new role, in the midst of 60+ hour weeks, motherhood came calling. Shefali was pregnant with her first child.

Redefining Good Work. Redefining Success

As a new mother, Shefali recalls— “getting in touch with parts of myself that I didn't know existed.” Pressed between the seams of profession and motherhood, she resigned from one of India’s leading employers in financial services to take stock of where life was leading.

Motherhood brought discipline—of time management and life-work boundaries. Shefali found herself making rules like, “I will not work longer than 40 hours and no more long commutes,” which is no mean feat in traffic-riddled Mumbai. Thus, during the heady years of the dot com boom, Shefali began her portfolio career in HR consulting, dictating billability and new parameters for success.

“Good work was no longer defined by where I worked, but the type of work.”Harvesting the First Gap

In 2003 the Salwan family expatriated to Netherlands to follow Sumeet’s rising career at Unilever. Fresh from being an in-demand HR consultant, 17 job applications and rejections later, Shefali experienced an abrupt loss of professional identity. “Gray winters. Being so far from friends and family and no work. Only when you don’t have something, do you realize how much you value it. I knew I could not be a stay-at-home mom.”

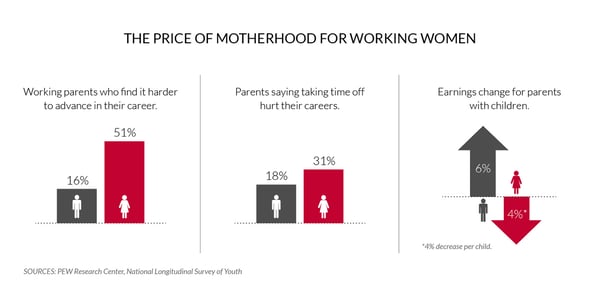

Shefali discovered, in a deeply personal way, that corporate time is not aligned with biological time. Despite sound organizational intentions, women pay for this trade-off at home and in the workplace. “35-42 are peak performance years for men. They can be for women as well, with the x-factor being maternity and other caregiving considerations,” Salwan reflects. The operating manual for leadership—the language on competencies, the expatriation cycle was not based on a woman’s clock. This perspective would inform much of Shefali’s later work in diversity & inclusion and in calibrating her own compass of life-work integration.

Diversity & Inclusion: From Initiative to Practice

In 2005, Shefali was recruited by Sandy Ogg to run a diversity and inclusion initiative at Unilever. The first conversation with company leadership on gender-based directional goals in talent recruitment and retention did not go far. The meeting ended early.

Gender-based directional goals are a tricky “chicken-and-egg conversation” for company leaders who have to walk a fine line of finding actionable roadmaps toward diversity and inclusion. From a narrative standpoint, directional goals on diversity run the risk of being interpreted as quotas, which can be disempowering for talent. But not articulating ambitions through clear and measurable outcomes can result in a company stopping at strategy.

“You cannot possibly go to market with a new product for instance, without articulating and pixelating ambition. So why should directional goals on diversity and inclusion be different?”Shefali walked this tightrope when facilitating conversations with leadership. She did this through— “deep listening and asking for change in a non-threatening fashion.”

One of the more gratifying outcomes from her tenure at Unilever was the emergence of diversity as practice. This methodology became embedded in all aspects of talent allocation and management from hiring and promotions to leadership development. The Global Diversity Board led by the CEO, of which Shefali was a member, oversaw policy and practice. Three years later, after her departure, Unilever received a Catalyst Award for gender diversity in recognition of its highly successful mentoring program and roll-out of flexible working. The mentoring program was conceived and designed as a key initiative that Shefali championed.

Coaching for performance and impact

In 2009, in the midst of a global financial crisis, the Salwan family relocated to Singapore. Across three years in England, Shefali had built a rich portfolio between executive coaching and HR consulting. Relationships, and a network of past clients from the days of financial services in India, made for an exciting transition and this Singapore chapter was one that Shefali remembers fondly.

During this time, Shefali added two executive coaching certifications to her portfolio through the Academy of Executive Coaching and the Newfield Network of Ontological Coaching. The Newfield Ontological framework, with its integrated approach of viewing life and work as one portfolio, resonated with Shefali. It would later influence her own work-life portfolio redesign when the next wave of change hit.

By the end of 2012, Shefali had coached C-Suite executives and NGO leaders in more than 45 countries including England, India, Malaysia, Singapore, and Africa. Her career had hit a local peak in value-creation and impact, stretching cross-cultural boundaries in countries as far as Azerbaijan, Mongolia and American Samoa.

Executive coaching affirmed Shefali’s enduring interest in catalyzing the generative potential of transformative leadership. But she was not finished yet.

Shefali Salwan’s journey continues in Part II of this series. Subscribe to our articles to find out where the river takes her next.