Welcome to part two of our five-part series on Connecting Talent to Value.

Previously, we talked about developing your value agenda in order to bend the curve dramatically upward. Now it's time to figure out precisely what roles have the most potential to deliver on this ambitious vision. During this process, we might find these key roles are not sitting nicely in the hierarchy where we thought they would be.

“The List” of Critical Roles

When I discovered that reassigning high performers to critical roles could bend the value curve exponentially upwards, I began introducing other Blackstone companies to the concept of “The List”, a collection of 25 to 50 of the most important roles in a company, the ones that really drive value. What was a “most important” role? If the work to be done by a person in a role either creates or enables a material chunk of value to be created, then that role connects to value and could be on the List.

Why not have 75 or 100 roles on The List? When we began to evaluate where value was being driven in a company, there typically weren’t that many spots unless we were going to go really “micro” on value. Depending on the size of the company and its global reach, rarely would there be more than 50 roles that were mobilizing the bulk of potential value. More often it was between 25 and 40. That’s not to say it couldn’t be more. When I was working at Unilever, for instance, we had done this exercise and ended up with 56 roles on our List.

When we began looking at roles in the context of the value agenda at Blackstone, we found two types were associated with crucial points of leverage. Value-creating roles were responsible for generating revenues, lowering costs, and increasing efficiency. Value-enabling roles were responsible for helping us manage value at risk. While value-creating roles focused on generating revenues and lowering costs, enabling roles typically lowered risks associated with the work of value creation. That is, they performed work which overcame hurdles like talent shortages, cybersecurity issues, regulatory compliance, and legal issues.

Both types of roles involved jobs that needed to be done to successfully deliver a significant portion of the value agenda; therefore, The List always included some of each.

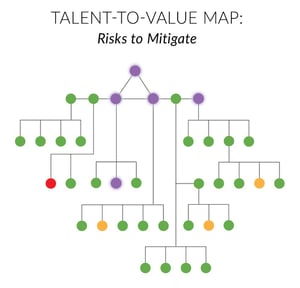

In focusing on roles rather than hierarchy, I broke with the traditional approach of using the top tier of the org chart as a proxy for value creation (as in the Traditional Talent Map below). We discovered that value-creating roles and value-enabling roles existed much deeper in the enterprise than might at first be suspected. Both types were showing up for us not just one layer below the CEO, but more often two and three below.

Before we even thought about what specific talents to place where, we got even more explicit about role requirements. We would sketch out a rough map of the value-creating roles in the company, including relevant value-enabling roles (see Talent-to-Value Map above). Next we quantified the specific contribution expected of each of these critical roles. This allowed us to identify the value “hot spots” (blue dots in the map) as places in the talent-to-value hierarchy where the roles really matter. Next we quantified the specific contribution expected of each of these critical roles. Then we’d assign each one a number based on the value we expected from that role (for example, $50M in EBITDA times the multiple). To deliver that particular chunk of value, we articulated a specific set of jobs to be done. Value-creating roles got 100% of the value they were aiming to create and value-enabling roles got a percentage based on the value at risk they were mitigating, plus an increment for value levers they would influence. If we had someone who couldn’t or didn’t get the job done in any of these roles, these numbers would give us clarity about how much value the company as a whole would have at risk.

What about those three dots forming the triangle at the top of the Talent-to-Value Map? They represent three roles that deserve special consideration: the CEO, the CHRO, and the CFO. This triumvirate forms what I call the “Golden Triangle” (our practical friends at McKinsey simply refer to this as the G3). When you have to run a company and change it—fast—these three roles must be filled with the absolute best talent you are capable of attracting, talent that must be able to do what needs to be done. Whether that’s leading a turnaround, a pack of M&As, or an accelerated growth spurt, you need people in these three roles who have not only the right experience and skills, but also the ability to lead together as a team. A lot of our time and energy at Blackstone was spent identifying and assembling the right triangle of CEO, CFO, and CHRO for each portfolio company.

Now we were ready to begin connecting the rest of the critical roles to the right talent. Stay tuned for the third part of this series where we discuss how to do exactly that.